Press release

, François-Xavier Branthôme

Portuguese tomato growers receive a total of more than EUR 16 million of aid per year, but a large part of this – around EUR 13.3 million – should decrease considerably after 2027. The country's industry has requested that the rules be applied in Portugal in the same way as in Spain or Italy.

Portugal ended its presidency of the European Union by reaching a political agreement on the new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which will be in force between 2023 and 2027. Farmers and the country's food industry operators are nonetheless far from reassured. In the case of the processing tomato sector, there is great concern about how the new rules will be implemented by each Member State. In the case of Portugal, the tomato processing sector is basically an exporting industry and, as such, it is highly exposed to international competition. This is why growers and processors alike are asking the government for aid to be allocated in a “fair” manner with regard to Spain and Italy, failing which Portugal “would permanently lose an industrial sector that is positioned fifth in the world, with exports valued at EUR 187 million.”

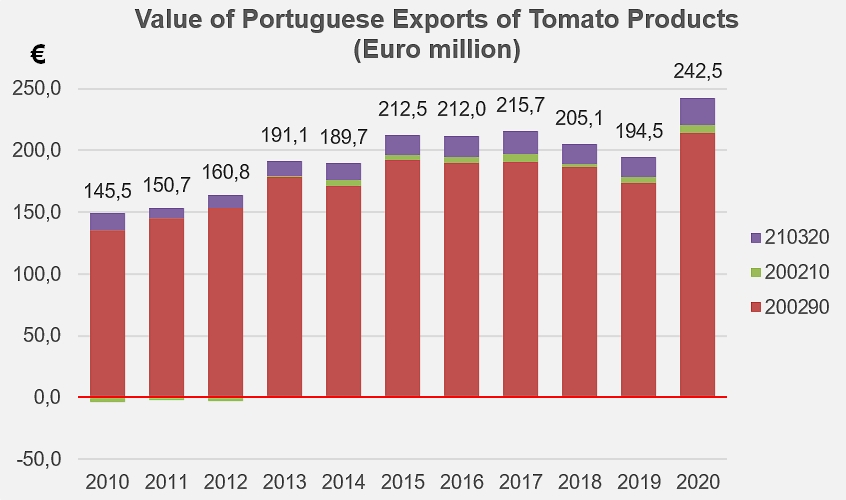

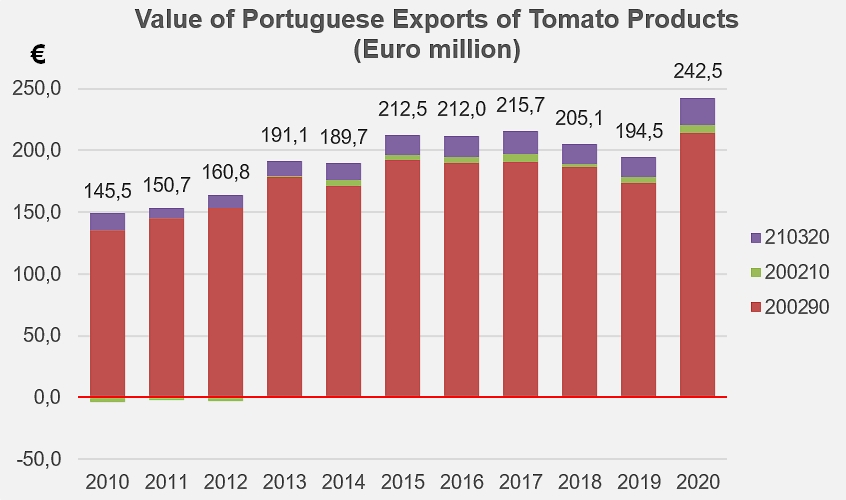

The value of exported products rose in 2019 to around EUR 190 million, and jumped to more than EUR 240 million in 2020 (source: TDM).

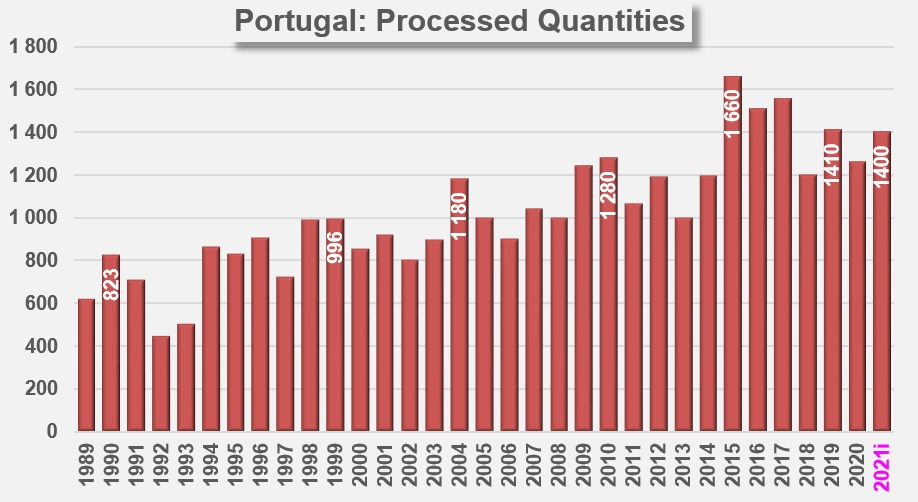

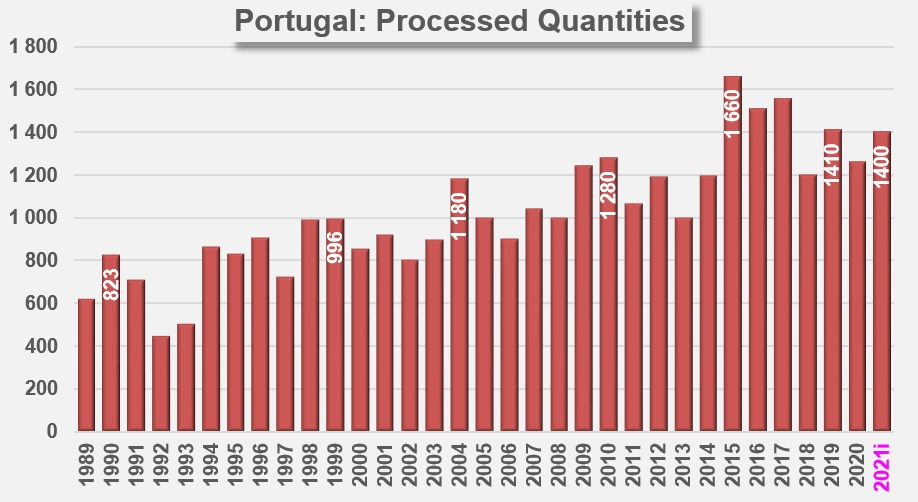

An Agroges study shows that the processing tomato sector has evolved “very favorably” over the past two decades, relying on “a significant increase in efficiency, productivity and relevance” in the irrigated area of the greater Ribatejo e Oeste region. During this period, surfaces planted with processing tomatoes increased by 27.4% and total production increased by 47.95%. Productivity increased 16.1% and production per grower increased 426.1%. This amounts to a total production of 1.440 million tonnes in 2019, produced by 367 growers on a total area of 14,468 hectares, generating a total turnover of EUR 119 million.

On the industrial side, according to local sources, the turnover amounted to EUR 248 million and the added value reached EUR 90 million. Exports totaled EUR 187 million (EUR 194 million according to statistical data collected by TDM, Ed.), with “an average productivity of EUR 110,000 per employee in the sector, 3.5 times higher than the average recorded by the food industry as a whole and 7.6 times greater than that of the agri-food sector,” indicated the Agroges study.

In 2019, in terms of aid, under the terms of the first pillar of the CAP, the country's tomato growers received more than EUR 16 million. Of this amount, only 3.3 million are designated as specific aid for the tomato sector under production-related payments (PLP). The remaining EUR 13.3 million fall under the basic payment system and the greening scheme (which will be replaced by the more demanding “eco-regime”: these are the amounts which, under the new CAP, should be drastically reduced. Aid linked to production, which amounts to EUR 236.5 per hectare, will most likely be maintained, according to representatives of the sector.

The objective of the new CAP is to put in place, by 2027, a convergence of basic payments to farmers, with part of the aid from the first pillar of the CAP – originally created for certain specific crops or produce such as maize, cereals, tomatoes or milk, among others – to be distributed equitably among all farmers with an eligible area, including sectors that until now have not received aid, like olives, almonds, walnuts, some fruits and vegetables, and even wine.

The target is that after 2027, all Portuguese farmers will receive, from this first pillar, a fixed amount per hectare, which will be around EUR 100 according to the scenario adopted, against a total EUR 522.60 per hectare paid currently on average, in the case of tomatoes. This reduction is expected to occur gradually, between 2023 and 2026.

For Manuela Nina Jorge, Managing Director of Agroges, this evolution of the CAP “will call into question the income of the farmers and, ultimately, their capacity for capitalization and investment.” In effect, the cost of inputs in Portugal, whether energy or agrochemicals, is “significantly higher” than in other European countries, and this, by nature, harms the competitiveness of the sector. The industry hopes that the government will put in place alternative measures, particularly in terms of the environmental impact of agriculture, which will help offset part of the loss announced. “Alternative measures are being studied in terms of eco-aid and subsidies,” specifies an authorized source.

But what producers really fear is that direct aid – payments linked to production – may be different in Portugal from what it is in Spain and Italy, jeopardizing a balance that is currently already fragile.

By the end of the year, the different Member States will define their National Strategic Plan for the CAP, the CAP NSP, which determines how each of them will use available funds. For tomato growers and processors, the main concern remains convergence with Spain and Italy. “Until today, fortunately, this has been the case, but it has to continue. Each penny that is deducted takes us further away from the market. Balance should be considered a priority,” says Gonçalo Escudeiro, from the National Federation of Producers' Organizations. “In the current context, the situations are relatively similar, but if Portuguese growers receive less aid than their Spanish or Italian counterparts after 2027, we will lose our competitiveness and the sector will relocate. The whole country would lose in that case,” underlined the executive, adding: “We cannot face further threats to our situation, because our balance today is already very precarious.”

There is also great apprehension on the industrial side. With the Sugal group, Portugal has the largest tomato processor in Europe and the second in the world, showing the extent to which the tomato paste market is competitive and global. Sugal, which is the only company in the world that conducts two tomato processing campaigns per year – thanks to investments it has made in Chile – ensures that the consolidation occurring within the sector over the last twenty years has been one of the elements that have enabled the industry to “adapt and acquire the necessary efficiency to be competitive on international markets.”

Sugal is the largest tomato processor in Europe and the second largest in the world. The company runs factories in Portugal, Spain and Chile.

Manuel Gonçalves, a member of the group's board of administrators, states that recent years have been “very demanding” in terms of price and profitability, so that the sector as a whole is in a “relatively delicate” economic and financial situation. For the executive, it is “very important to maintain the features and nature of the aid allocated to growers, with a view to maintaining the competitiveness of the sector at the international level.”

Manuel Gonçalves has pointed out that no one plants tomatoes for processing if there is no processing industry and vice versa, because “it is not viable to go and buy tomatoes in Spain to process them in Portugal.” Proof of this is the investment that Sugal made in Spain, with the purchase of a factory in Seville. This is the reason why the head of the group insists on the need for an ecosystem (in the sense of an economic system, Ed.) that is “well built and competitive” at each stage of the process. This also requires an implementation of the CAP that is similar to the way it is done in other European countries. “The instruments may vary, but overall, at the end of the day, the impact that this aid will have on national farmers will have to reflect what is happening in other countries,” he argues.

And a relocation scenario is clearly a possibility. “As tomatoes is not a transportable product, it is clear that a structural and definitive loss of competitiveness in a given country will always lead us to think about the direction we must take next, the place where we must relocate, and cause us to focus our efforts and resources on maintaining and continuing to acquire the competitiveness that is essential to operate in this sector,” explained Gonçalves, who points out that, “although it is the second largest company [for this sector] in the world, Sugal still remains a relatively small company, with a 5% share in a very fragmented and competitive market.” And many jobs are potentially at stake since, at the peak of production, Sugal employs around two thousand people in the factories in Ribatejo. The group's turnover amounts to around EUR 280 million per year.

“Portugal has already demonstrated that it is a competitive country for this industrial sector; we believe that it will continue to be so and, if this is the case, Sugal will continue to invest and develop in Portugal,” stated Manuel Gonçalves. For this, it needs to institute a “scenario of stability and predictability” in terms of a regulatory and fiscal framework. “We are totally convinced of the need to implement an increasingly sustainable agricultural and industrial practice in terms of emissions and consumption of resources, but this effort must be supported in the same way as in other sectors,” he added.

Sugal also regrets that the European Union requires its companies to comply with very restrictive sustainability and environmental rules, but does not demand compliance with the same rules when products enter the European space. “We agree with the requirements imposed on us, but they come at a cost and involve investments. The problem cannot be solved by relaxing the rules at the European level, but it needs comparable market and competition conditions for everyone. As to the instruments required, that is up to the experts to determine. What matters is that we are consistent,” pointed out Manuel Gonçalves.

Gonçalo Escudeiro, from the National Federation of Producers' Organizations, considers that “either the EU protects its growers, or it must tax very aggressively international production entering the European market.” The next CAP will be quite demanding from an environmental point of view, “and that is very good,” he argues, but it is necessary to ensure that “it does not come at the cost of a loss of competitiveness for European producers.” One of the requirements of producers is that consumers should be able to know the origin of food products.

“Why does a garment that you buy have to mention its origin, while the same is not required for a tin of tomatoes or sweet corn, or a carton of milk?”

Some additional information

Source: dinheirovivo.pt