EU ETS drove a 4% reduction in European emissions between 2008 and 2016

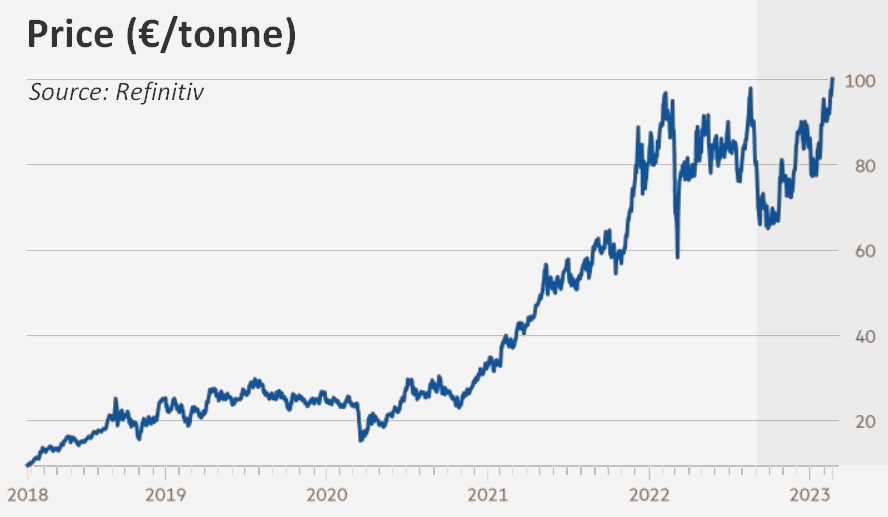

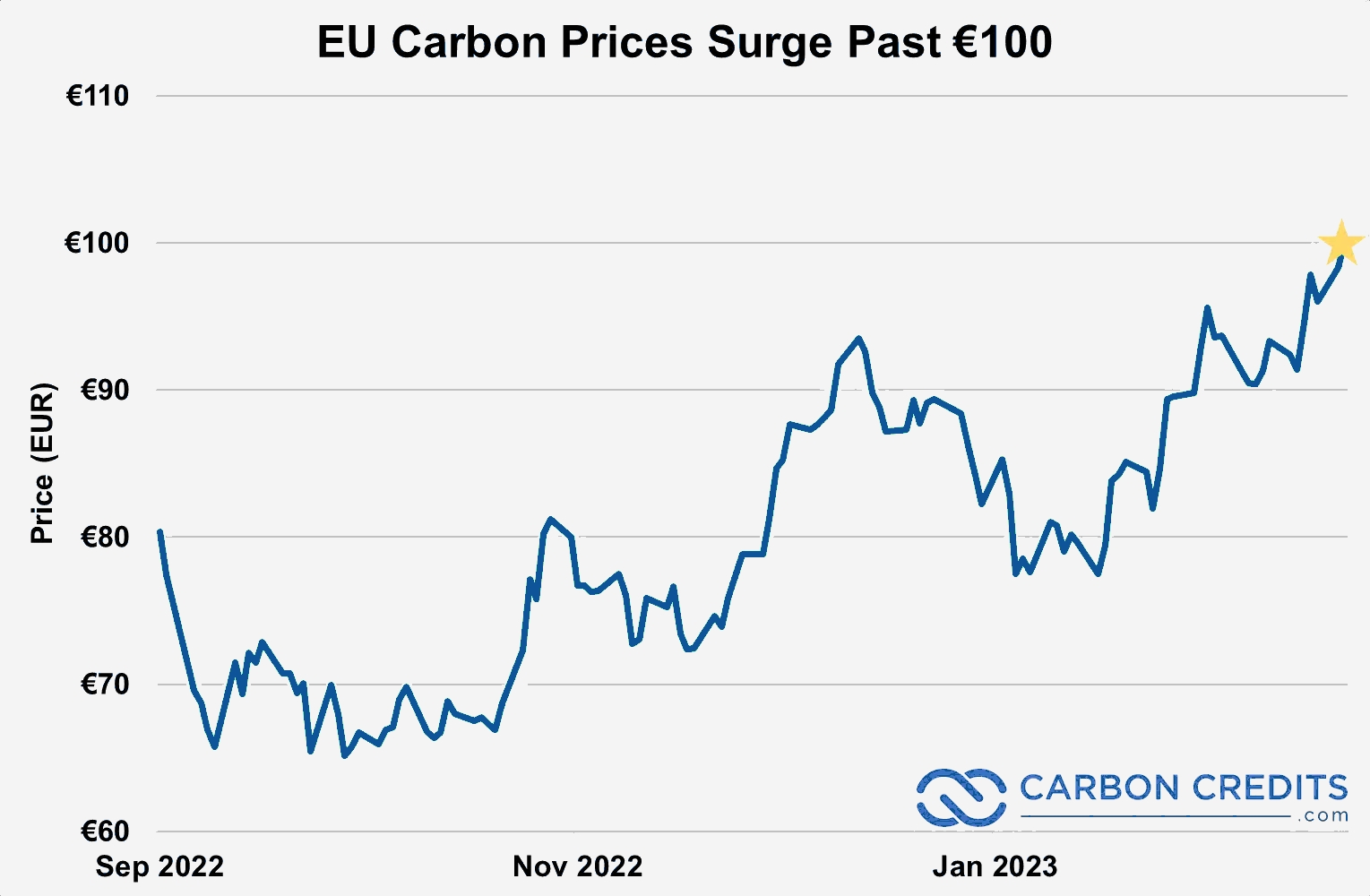

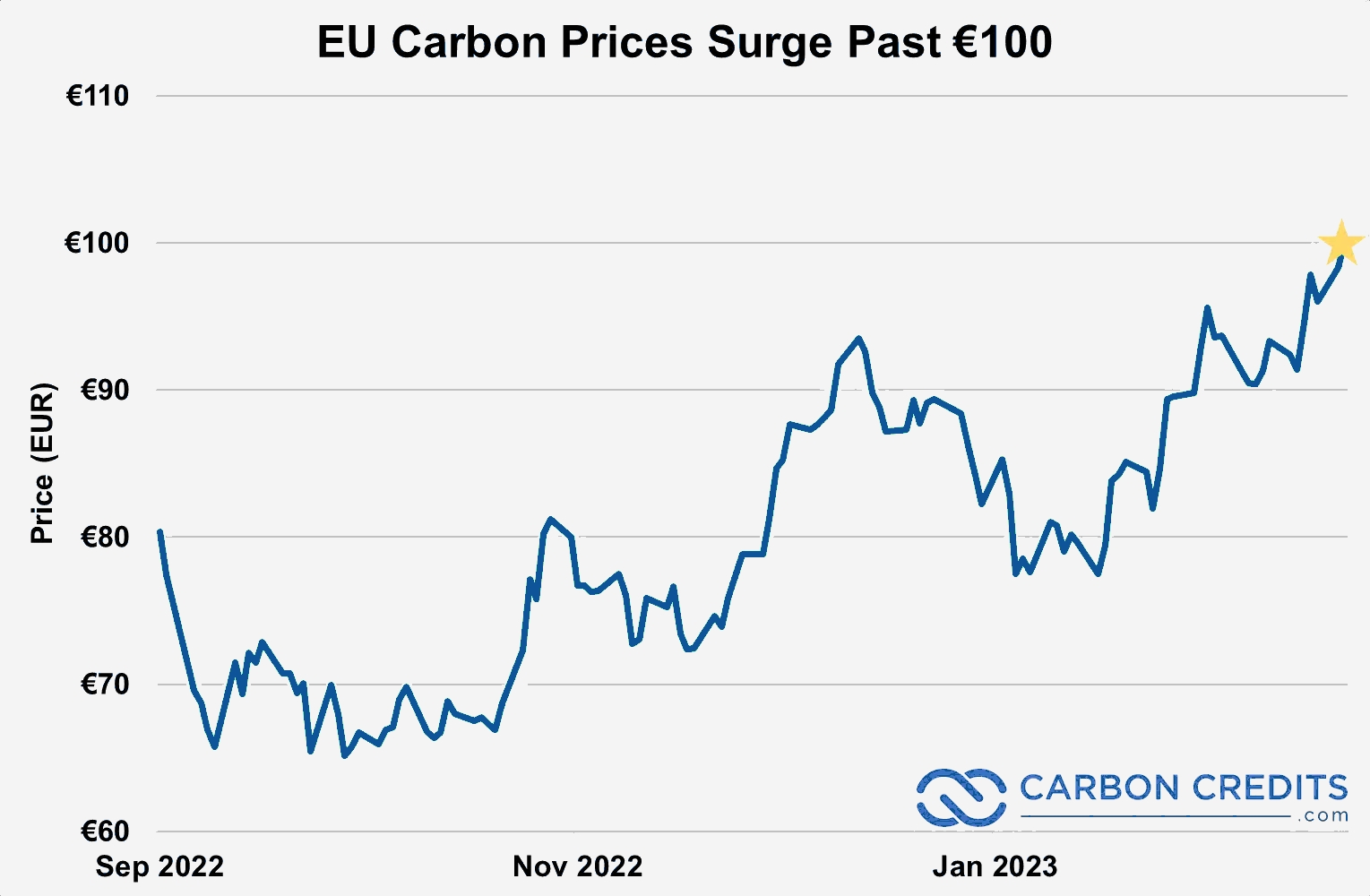

The price of permits on the European Union's carbon market hit 100 euros (USD 106.57) per tonne for the first time on February 17, 2023, a milestone that reflects the increased costs that factories and power plants must pay when they pollute.

EUAs are the main currency in the European Union's Emissions Trading System (ETS) that forces manufacturers, power companies and airlines to pay for each tonne of carbon dioxide they emit as part of the bloc's efforts to meet its climate targets.

The price of carbon credits in the system — a core part of the bloc’s net zero strategy, which aims to put a price on pollution — has risen fivefold in the past three years, and gains have accelerated in recent weeks as the EU has tightened rules to make the system more onerous for polluters.

“The fundamental point about this market is the EU has cleared the way for higher prices as that is what is ultimately needed to meet their aims of cutting emissions,” said Mark Lewis, head of climate research at hedge fund Andurand Capital Management. New rules agreed in December and in the process of being ratified, which will effectively see emissions allowed under the scheme falling to zero by 2039, are the “long-term structural bullish driver of this market”, added Lewis.

EU lawmakers gave initial approval this year to rules that would make the system tougher. The total number of allowances in the system will fall over time, and the number given out to polluters for free will also fall.

Some analysts said the €100 threshold would incentivize investments in emerging clean technologies such as carbon capture and hydrogen, but major polluters warned of the impact that higher carbon prices might have on their businesses and on their ability to make investments.

Jori Ringman, director-general of the Confederation of European Paper Industries, said the price jump “will affect the competitiveness of the EU’s manufacturing sector”, while the European Steel Association said high prices were “worrying in the current EU context of economic uncertainty and fragility”.

Peter Liese, the European parliament’s lead negotiator on the EU ETS, said in February that it was a “very important point” to “keep industry inside Europe and to help them decarbonize”. However, if companies did not decarbonize over the coming years, “there will be scarcity of allowances and that will increase the price”.

An academic study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2020 found that the EU ETS drove a 4% reduction in European emissions between 2008 and 2016. But progress has mainly been made in the power sector, as generators have switched from fossil fuels to renewables. Solutions for “hard to abate” sectors, such as cement and steel, are typically more expensive and remain in their infancy.

The world’s top climate scientists said last year in a sweeping UN report that climate mitigation solutions costing USD 100 per tonne of carbon or less “could reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by at least half the 2019 level by 2030”.

Sources: Reuters, Financial Time, carboncredits