Respect for your privacy is our priority

The cookie is a small information file stored in your browser each time you visit our web page.Cookies are useful because they record the history of your activity on our web page. Thus, when you return to the page, it identifies you and configures its content based on your browsing habits, your identity and your preferences.

You may accept cookies or refuse, block or delete cookies, at your convenience. To do this, you can choose from one of the options available on this window or even and if necessary, by configuring your browser.

If you refuse cookies, we can not guarantee the proper functioning of the various features of our web page.

For more information, please read the COOKIES INFORMATION section on our web page.

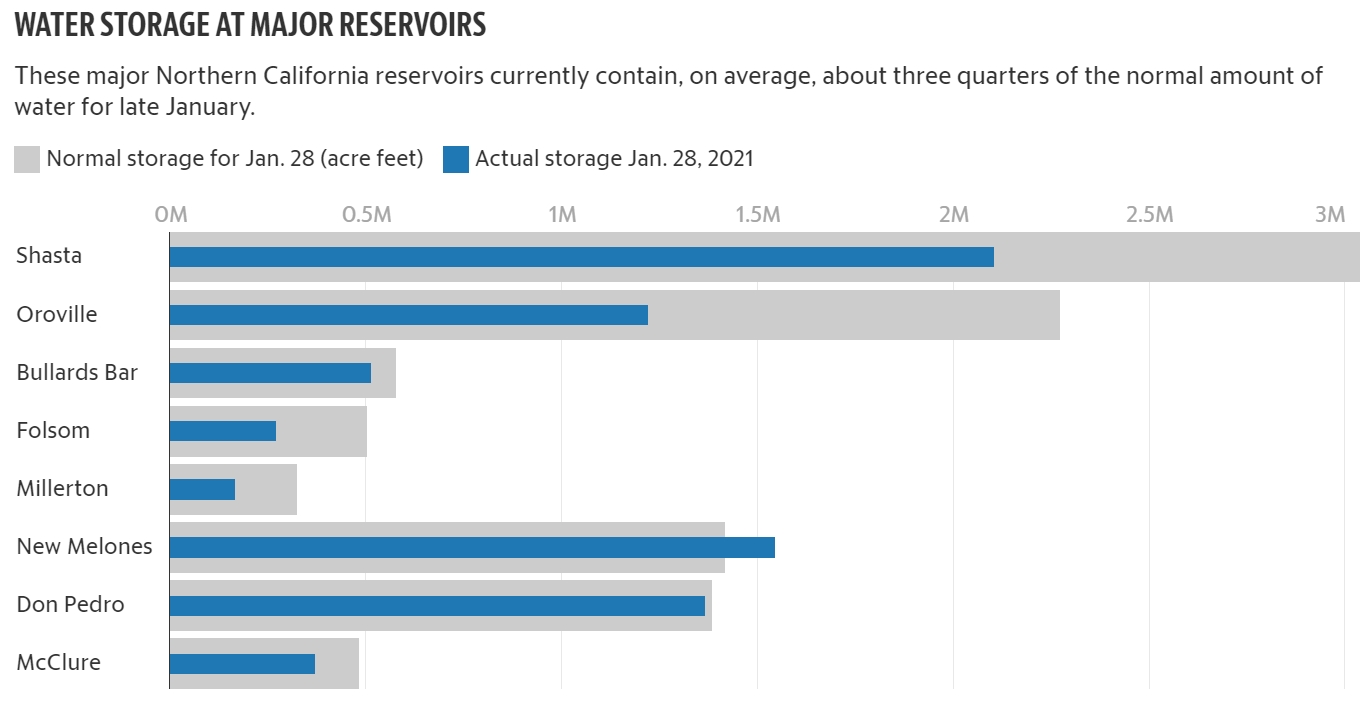

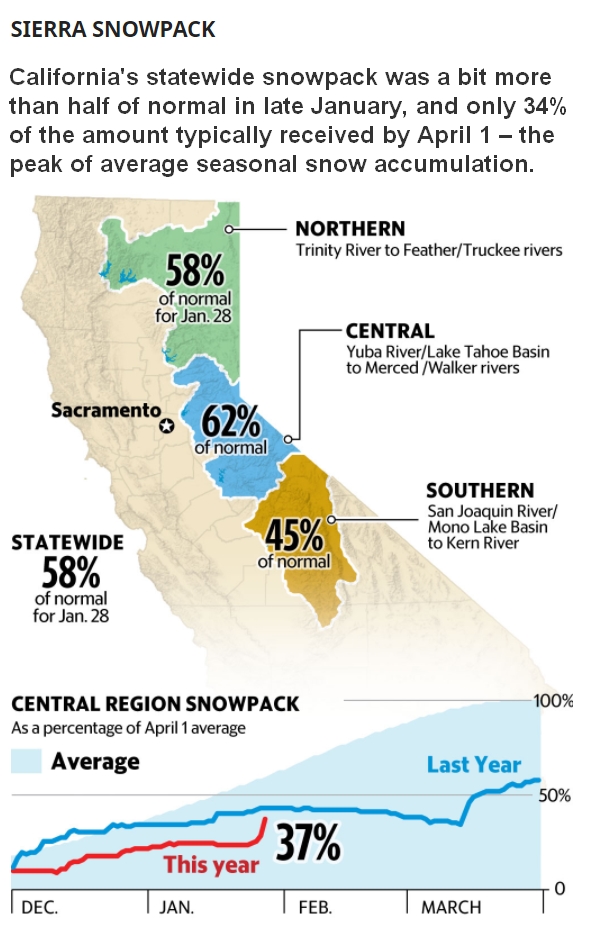

So far this season, the state has received only a few small or moderate “atmospheric river” storms. Atmospheric rivers form when high-powered winds drag a fire hose of tropical moisture across the surface of the Pacific Ocean, producing 500-mile (800 km) wide conveyor belts of water that can last for days. The largest storms can produce as much rain as a major hurricane; in a typical year, they provide nearly half of the state’s annual precipitation. They can cause major floods, and, in 2017, contributed to the emergency at Oroville Dam that prompted the evacuation of 188,000 residents.

So far this season, the state has received only a few small or moderate “atmospheric river” storms. Atmospheric rivers form when high-powered winds drag a fire hose of tropical moisture across the surface of the Pacific Ocean, producing 500-mile (800 km) wide conveyor belts of water that can last for days. The largest storms can produce as much rain as a major hurricane; in a typical year, they provide nearly half of the state’s annual precipitation. They can cause major floods, and, in 2017, contributed to the emergency at Oroville Dam that prompted the evacuation of 188,000 residents.

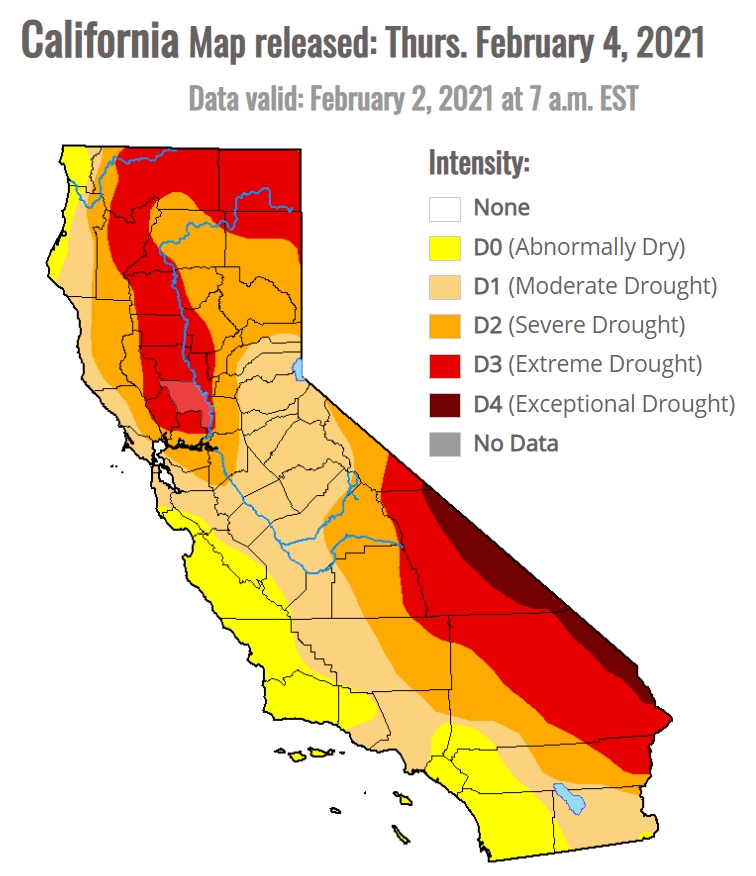

Despite being officially over since spring 2017, the effects of drought are still being felt. The drought has left water supplies in much of the San Joaquin Valley in desperate shape, even after it officially ended.

Despite being officially over since spring 2017, the effects of drought are still being felt. The drought has left water supplies in much of the San Joaquin Valley in desperate shape, even after it officially ended.