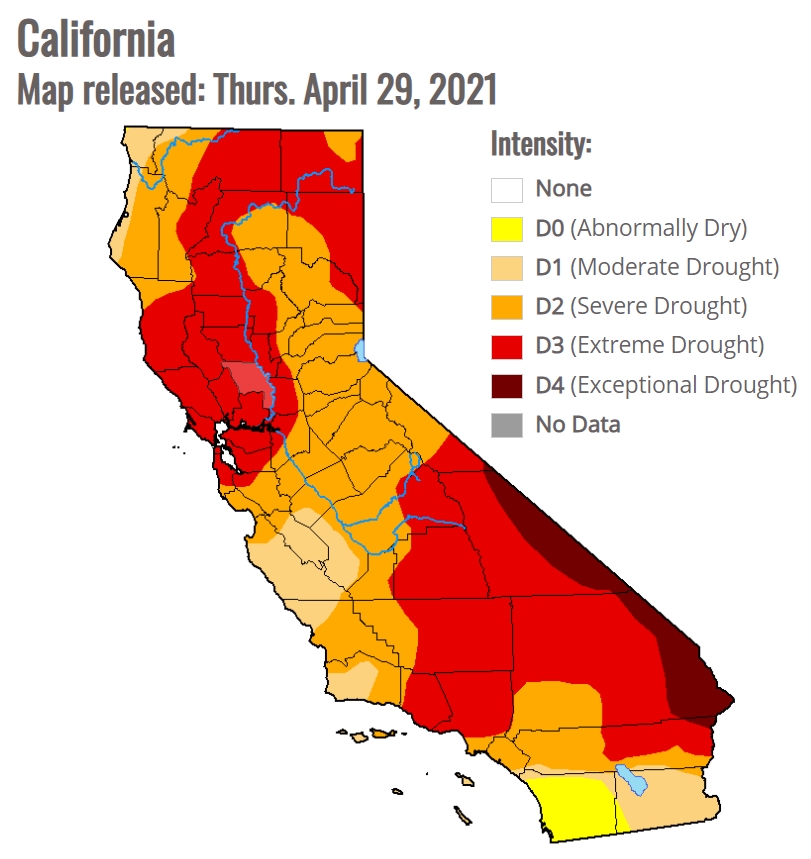

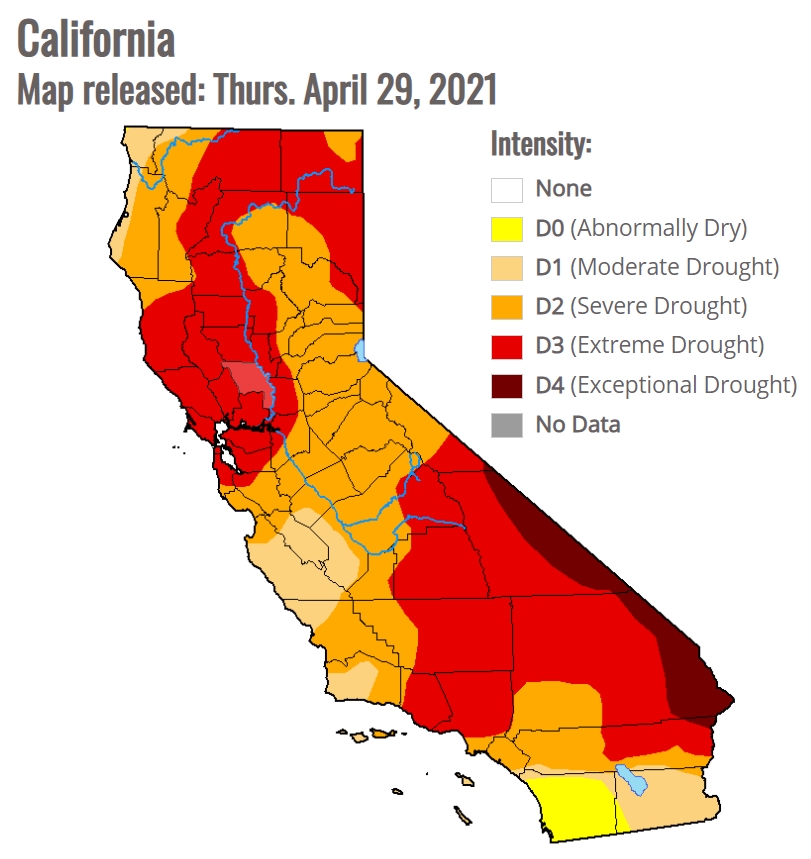

California is in the second year of a drought. Governor Newsom made his first drought declaration at the end of April.

How dry is it?

Precipitation – Northern California has received about 48% of average historical precipitation for this time of year. This is the 3rd driest water year on record, so far. Only 1924 and 1977 were drier in precipitation over the last 101 years. At this time of year, there will probably be little more precipitation until fall.

Precipitation – Northern California has received about 48% of average historical precipitation for this time of year. This is the 3rd driest water year on record, so far. Only 1924 and 1977 were drier in precipitation over the last 101 years. At this time of year, there will probably be little more precipitation until fall. Snowpack – Statewide snowpack is about 30% of average for this date. Snowmelt will only help reservoir storage a little this year.

Snowpack – Statewide snowpack is about 30% of average for this date. Snowmelt will only help reservoir storage a little this year. Temperatures – Temperatures have been warmer than historically, and we should watch how they develop over the year. In the 2012-2016 drought, warmer temperatures increased evaporation and dried soils much more quickly, further reducing streamflows, groundwater recharge, and stressing already-dry forests and aquatic ecosystems.

Temperatures – Temperatures have been warmer than historically, and we should watch how they develop over the year. In the 2012-2016 drought, warmer temperatures increased evaporation and dried soils much more quickly, further reducing streamflows, groundwater recharge, and stressing already-dry forests and aquatic ecosystems. Surface water runoff – With warmer temperatures, this year might develop to rank drier in streamflow than precipitation, but it is too early to tell yet. Historically, precipitation this low would lead to Sacramento Valley annual streamflow of about 5-6 million acre-ft, compared to an average of about 18 million acre-ft., more than 2/3 loss of average surface water available.

Surface water runoff – With warmer temperatures, this year might develop to rank drier in streamflow than precipitation, but it is too early to tell yet. Historically, precipitation this low would lead to Sacramento Valley annual streamflow of about 5-6 million acre-ft, compared to an average of about 18 million acre-ft., more than 2/3 loss of average surface water available.  Reservoir storage – Statewide, reservoirs are at about 74% of their long-term average. Last year was dry, and this year’s runoff hasn’t helped. Official records show the major Sacramento Valley reservoirs are all quite low. Shasta, Oroville, Folsom, and New Bullards Bar are all lower today than they were on this date in any year of the 2012-2016 drought. This is especially concerning as this drought seems to be off to a faster start than the 2012-2016 drought.

Reservoir storage – Statewide, reservoirs are at about 74% of their long-term average. Last year was dry, and this year’s runoff hasn’t helped. Official records show the major Sacramento Valley reservoirs are all quite low. Shasta, Oroville, Folsom, and New Bullards Bar are all lower today than they were on this date in any year of the 2012-2016 drought. This is especially concerning as this drought seems to be off to a faster start than the 2012-2016 drought.

Some likely implications

Some likely implications The drought could end quickly, or it could go on for several more years.

Cities seem mostly well prepared for this drought with stored surface and groundwater, and water banking and purchase agreements with farmers. They have continued drought preparation and water conservation efforts since the last drought. Urban water use is only 20% of all water diversions, so conservation mostly tends to help cities bank water for later, but isn’t bad for others either.

Agriculture is a much greater water user and has less banked water, but still has access to considerable groundwater, which compensated for about 70% of lost irrigation water in the previous drought. Water markets and selective fallowing will further reduce the economic impacts of remaining agricultural shortages, as they did in the previous drought. Some farmers surprised by shortages in the 2012-2016 drought should be better prepared for this one, so far. Droughts these days are tougher on agriculture than cities, given their relative water demands and greater difficulties preparing irrigated agriculture for drought, especially with the growing share of more profitable, but hard-to-fallow, permanent crops.

Groundwater always becomes a problem during drought, with less surface water inflows and much more pumping, mostly for agriculture. Users of shallower rural wells suffer most directly from this. This drought will make implementing the State’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) for ending groundwater overdraft much more difficult, but also provide opportunities for local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies and state regulatory agencies (DWR and SWRCB) to provide more forceful and specific guidance and motivations for implementing practical and effective local groundwater management.

Rural drinking water supplies always worsen with drought. This process will continue in every drought until SGMA is well-implemented and better support exists for rural water systems. A few rural water systems have been connected to more secure supplies since the last drought and quite a few deeper wells have been drilled.

Ecosystems have the greatest difficulty preparing for drought, so they are the most vulnerable. In California’s highly variable climate, ecosystems are declining. Forest ecosystems will be stressed by drier and warmer-drier conditions, leading to greater spread of tree diseases and insect infestations. The previous drought killed over 100 million trees in California and increased catastrophic wildfires for several years after the drought, with wildfire damages and loss of life far greater than all traditional drought damages combined.

Millions of groundwater wells could run dry worldwide

Millions of groundwater wells could run dry worldwideBut the problem of drought is not limited to California alone. Millions of drinking wells around the world may soon be at risk of running dry. Overpumping, drought and the steady influence of climate change are depleting groundwater resources all over the globe, according to new research. As much as 20% of the world’s groundwater wells may be facing imminent failure, potentially depriving billions of people of fresh water.

“We found that this undesirable result is happening across the world, from the western United States to India,” said Debra Perrone, a water resources expert at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and co-author of a recent study.

The research found that millions of the wells extended less than 5 meters (about 16 feet) below the water table, putting them at risk of running dry. At least 6% of them, and potentially as much as 20%, appear to be in jeopardy. Those last few meters can dry up quickly, especially in places already stricken by drought.

“In areas where we see extreme rates of groundwater depletion, groundwater levels can decline on the order of a meter or more a year," co-author Scott Jasechko said.

In some places, including parts of the drought-stricken western United States, it’s already happening. Residents of California’s Central Valley are preparing for another arid summer and the rising risk of dry wells, The Fresno Bee reported in late April. It’s a recurring pattern there. Studies suggest that thousands of wells in interior California have run dry over the last decade or so, under long-lasting drought conditions.

In a separate study published last year Jasechko and Perrone suggest that thousands of wells across the Central Valley ran dry between 2013 and 2018 alone. That’s a big threat to rural California communities, where at least 1.5 million people rely on groundwater wells.

These concerns are only growing as climate change worsens the risk of severe drought in California and other arid regions around the world.

Source: californiawaterblog.com, scientificamerican.com