“Covering up soil in the American Fertile Crescent to harvest nothing but sunshine…”

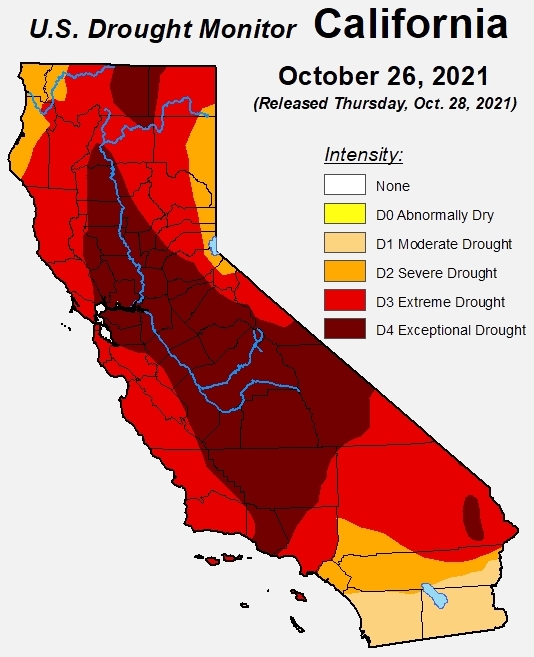

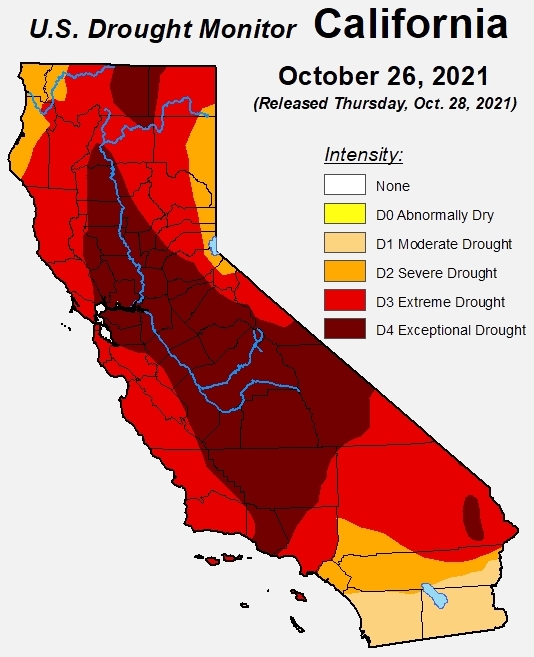

California's water bucket is not even half full as the state enters the 2022 water year, which began Oct. 1.

Two years of drought has depleted the state's surface and groundwater supplies, and weather forecasters predict a La Niña climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean, which has brought drought conditions in the past. "Model estimates by scientists suggest 140% of average precipitation would be needed just to generate average runoff," California State Climatologist Michael Anderson said. "It is important to get as much benefit out of these events to mitigate against the expected seasonal shortcomings."

An uncertain water supply for the coming year has farmers, water managers and water officials planning for all scenarios.

Kern County almond farmer Jenny Holtermann, who grows almonds in water districts served by the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, said her farm was affected by drought this year. "With limited water availability, it made more sense to remove the acres now. We will fallow the land for a year and hope to replant in fall in 2022 if the water outlook appears more promising."

Kern County almond farmer Jenny Holtermann, who grows almonds in water districts served by the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, said her farm was affected by drought this year. "With limited water availability, it made more sense to remove the acres now. We will fallow the land for a year and hope to replant in fall in 2022 if the water outlook appears more promising."

Jeanine Jones, California Department of Water Resources drought manager and interstate resources manager, said that state water agencies are doing a lot of contingency planning for potentially a very dry year.

Jones said she expects the SWP and CVP water projects will have low water allocations for water contractors. The SWP initial allocation, which is made on Dec. 1, will likely be very low, she said, because it is based on water available now. In discussing the SWP reservoirs, she said, "Oroville is at a record low storage and San Luis is not far behind in terms of record low."

For its part, Stuart Woolf, a large almond and tomato producer, recently bulldozed 400 acres (162 ha) of almond orchards in central California - about 50,000 trees that under normal conditions would have produced USD 2.5 million (Euro 2.15 million) of nuts every year for another decade. It's a fraction of the 25,000 acres (10,120 ha) his family farms, but razing the land was a necessary triage - "Like cutting off your horribly infected hand to keep the rest of the body going” he said.

Woolf plans to replace the trees with cover crops he'll neither sell nor harvest, but will use to sequester greenhouse gasses in his soil. He's setting aside other land for another kind of farming: industrial solar.

Woolf is among thousands of U.S. farmers whose businesses have been both damaged and transformed by historic drought and heat in recent months. And it's just the beginning. Climate change is having an impact on agriculture more grave than that of the Coronavirus pandemic, and far more chronic and complex - driving a paradigm shift in the business of food.

"We're at a crossroads - there's no turning back from here. No return to normal” said Don Cameron, president of California's Food and Agriculture Board and general manager of Terranova Ranch. "Right now there are more farms for sale in Central California than I've seen in my lifetime."

Producers must devise new strategies for their land: what to grow and where to grow it. Consumers will have to adjust to price increases even steeper than during the pandemic - and perhaps a less consistent supply of their favorite foods. Lawmakers will need to provide subsidies to support the transition, especially for small and midsize farms.

Producers must devise new strategies for their land: what to grow and where to grow it. Consumers will have to adjust to price increases even steeper than during the pandemic - and perhaps a less consistent supply of their favorite foods. Lawmakers will need to provide subsidies to support the transition, especially for small and midsize farms.

Farmers across North America should take heed of Woolf's journey, as they're likely to follow a similar path in the years to come. More frequent and violent storms are flooding fields and crippling distribution infrastructure in the South and Midwest; droughts and wildfires have battered farms and ranches; shifting seasons, temperature swings and invasive insects are taking a heavy toll nationwide.

It was heat and drought that first sickened Woolf's almond trees. The dry conditions pushed the cost of clean surface water to as much as $2,500 an acre-foot (or Euro 1.75/m3) - 10 times more than usual. Woolf knew much of his well water had turned salty, and would kill his almond trees. His best option was letting the orchards go and using the water from his good wells for his more profitable tomatoes.

When Woolf's father ran the farm, a single question guided him: What crops do I plant to optimize some of the most productive and versatile farmland in the world? Now Woolf is guided by a different calculus: Which crops will be most profitable per acre-foot of water invested? And how can he make the most of land that no longer supports crops?

When Woolf's father ran the farm, a single question guided him: What crops do I plant to optimize some of the most productive and versatile farmland in the world? Now Woolf is guided by a different calculus: Which crops will be most profitable per acre-foot of water invested? And how can he make the most of land that no longer supports crops?

In addition to razing his almond trees, Woolf had to fallow a third of his family's 25,000 acres. He began scouting land in less drought-strapped regions of California, and also in Portugal, where he can grow the same crops in less fertile soil but with more abundant water. His team is also changing the cropping patterns on his fields, adopting new drought-tolerant and heat-resistant varietals and adding a test plot of agave cactus - which thrives in the desert - for making liquor.

Based on his new reckoning, Woolf dedicated 1,300 acres (526 ha) of his land to a solar installation scheduled to come online in February. It's hard to imagine covering up soil in a region once considered the American Fertile Crescent to harvest nothing but sunshine, yet that's the plan. Woolf will reap about $1,000 an acre (Euro 2,471/ha) annually from leasing his land, and he'll be able to irrigate his other fields - a value of about $500 an acre (Euro 1,236/ha).

Woolf plans to expand his solar projects to 3,000 acres (1,214 ha) by 2025, and hopes eventually to be paid for sequestering carbon. He reasons that as water supplies dwindle and he grows less food, the prices for his specialty crops will rise, stemming his revenue losses. By the end of the decade, he estimates, a quarter of his revenue could come from non-food-related use of his land, like solar.

Woolf is one of thousands of California farmers trying to adapt and survive. This summer, Joe Del Bosque, who farms 2,000 acres (809 ha) of fruits and vegetables near Woolf, ripped out his asparagus crop to save his cantaloupes - protecting his melon market share. Alan Boyce of Materra Farming Inc. chose not to plant his tomato crops so he could share the water for that crop with his citrus-farming neighbors. At Terranova, where Cameron farms 9,000 acres (3,642 ha), he drilled deeper wells and expanded infrastructure to capture floodwater for future use when the rains return.

Yet Woolf, Boyce, Cameron and Del Bosque run large operations that can absorb losses and adapt. Smaller farmers will need more government help to survive. California Governor Gavin Newsom provides a promising model for climate-smart agriculture funding, backing new programs that ink emissions reductions to water-efficiency projects, and helping small and mid-size farms adapt to climate pressures.

It's hard to comprehend the immense stakes as climate change upends decades of custom. Central California grows nearly half of all the fruits, nuts and vegetables in the U.S., and a third of the world's tomatoes. Yet predictions for this region are grim: as of October 9, 2021, California's 2021 tomato yields were expected to fall 20% below normal; almond production is down about 15%; many vineyards have lost a third or more of their wine grapes. Prices will rise up to 25% for some of California's fall crops, according to Cameron, and the drought could hurt production well into 2023.

Farming has always been a perilous industry, but now it's facing levels of risk never seen before. Obviously, CoVid rattled our food system, but climate change could be a seismic shock. This is literally a kitchen-table issue, and industry leaders, voters, investors and policy makers need to begin treating it as such.

Sources: bloombergquint.com, washingtonpost.com, apnews.com, agalert.com

Kern County almond farmer Jenny Holtermann, who grows almonds in water districts served by the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, said her farm was affected by drought this year. "With limited water availability, it made more sense to remove the acres now. We will fallow the land for a year and hope to replant in fall in 2022 if the water outlook appears more promising."

Kern County almond farmer Jenny Holtermann, who grows almonds in water districts served by the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, said her farm was affected by drought this year. "With limited water availability, it made more sense to remove the acres now. We will fallow the land for a year and hope to replant in fall in 2022 if the water outlook appears more promising." Producers must devise new strategies for their land: what to grow and where to grow it. Consumers will have to adjust to price increases even steeper than during the pandemic - and perhaps a less consistent supply of their favorite foods. Lawmakers will need to provide subsidies to support the transition, especially for small and midsize farms.

Producers must devise new strategies for their land: what to grow and where to grow it. Consumers will have to adjust to price increases even steeper than during the pandemic - and perhaps a less consistent supply of their favorite foods. Lawmakers will need to provide subsidies to support the transition, especially for small and midsize farms. When Woolf's father ran the farm, a single question guided him: What crops do I plant to optimize some of the most productive and versatile farmland in the world? Now Woolf is guided by a different calculus: Which crops will be most profitable per acre-foot of water invested? And how can he make the most of land that no longer supports crops?

When Woolf's father ran the farm, a single question guided him: What crops do I plant to optimize some of the most productive and versatile farmland in the world? Now Woolf is guided by a different calculus: Which crops will be most profitable per acre-foot of water invested? And how can he make the most of land that no longer supports crops?