Officials are “actively planning for another dry year” in 2023

Shoppers are already hurting from grocery store inflation of 13.5 %, and California's drought is pushing prices of tomatoes, onions and other stricken crops up further still. Price hikes have hit canners and processors, consumers will be affected in the coming months.

California's three driest years on record have seen wells dry up, farmland lie fallow and wildfires ravage hillsides ; officials say they are “actively planning for another dry year” in 2023

A lack of rain and snow in central California and restricted water supplies from the Colorado River in the southernmost part of the state have withered summer crops like tomatoes and onions and threatened leafy greens grown in the winter. That has added pressure to grocery prices, putting a squeeze on wallets with no end in sight.

The rise in food prices this year has helped drive U.S. inflation to its highest levels in 40 years. California's drought conditions, on top of Hurricane Ian ravaging citrus and tomato crops in Florida, are likely to push food costs even higher. Drought in an area known as the U.S. salad bowl has not only impacted fresh produce, but also pantry staples like pasta sauce and premade dinners. "There's just not enough water to grow everything that we normally grow," said Don Cameron, President of the California State Board of Food and Agriculture. Cameron also grows processing tomatoes, onions, garlic and more than a dozen other crops near Fresno, California.

The most recent drought in California began in 2020, worsening when California's Central Valley faced its driest January and February in recorded history. Snowpack, supplying surface water for much of the Central Valley, reached just 38% of its historic average by April, according to the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency focused on conservation efforts.

Near Firebaugh, California, Aaron Barcellos planted just a quarter of the 2,000 acres of his family's fourth generation farm. This summer, he harvested tomatoes two weeks early to prevent further drought damage. "I don't think farming in California has ever been more complex and more challenging, and the drought is a large part of that," said Barcellos.

Near Firebaugh, California, Aaron Barcellos planted just a quarter of the 2,000 acres of his family's fourth generation farm. This summer, he harvested tomatoes two weeks early to prevent further drought damage. "I don't think farming in California has ever been more complex and more challenging, and the drought is a large part of that," said Barcellos.

California produces about 27% of the world's processing tomatoes, but in August the U.S. Department of Agriculture cut its 2022 forecast to 9.52 million metric tonnes (10.5 million short tonnes), down 10% from its 11.07 million mT (12.2 million sT) estimate earlier in the year.

Because of the shortfall, farmers this year negotiated higher prices for tomatoes, as well as onions and garlic used for spices in countless boxed meals and other grocery store staples, Cameron said. "What you're seeing harvested this summer, that really hasn't even hit the grocery shelf, is a 25% increase in the cost of the product to the processors – the canners, the buyers downstream," he said. "The onions and garlic have already been negotiated for 2023, with another 25% increase in price."

Cameron said tomato prices face a similar hike, resulting in a 50% increase in cost to canners and processors from 2021 to 2023. Ketchup and other tomato-based pasta sauce maker Kraft Heinz Co said it is sourcing tomatoes from other regions to make up for California's shortfall. A company spokesperson said Kraft could guarantee tomato supplies in grocery stores, but did not rule out price increases.

California has seen the driest January-to-March period in at least a century, as well as record amounts of rainfall in October — a so-called 'whiplash' weather effect that is set to become more common as the planet heats up. Snowfall along California’s mountain ranges typically provides one-third of the state’s annual water supply, but last year’s snow levels were far below average. The Colorado River is also beset by drought, reducing supplies to southern California.

Precipitation was 76 percent of average for the year that just ended, and the state’s reservoirs are at 69 percent of their historical levels, state officials said. Most of California is in severe or extreme drought, the US Drought Monitor says. The worst conditions are throughout the Central Valley, the state’s agricultural heartland where many of the nation’s fruits, vegetables and nuts are grown.

Rural communities are losing access to groundwater as heavy pumping depletes underground aquifers. More than 1,200 wells have run dry this year statewide, a nearly 50 percent increase over the same period last year, according to the California Department of Water Resources. Fewer than 100 dry wells were reported annually in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

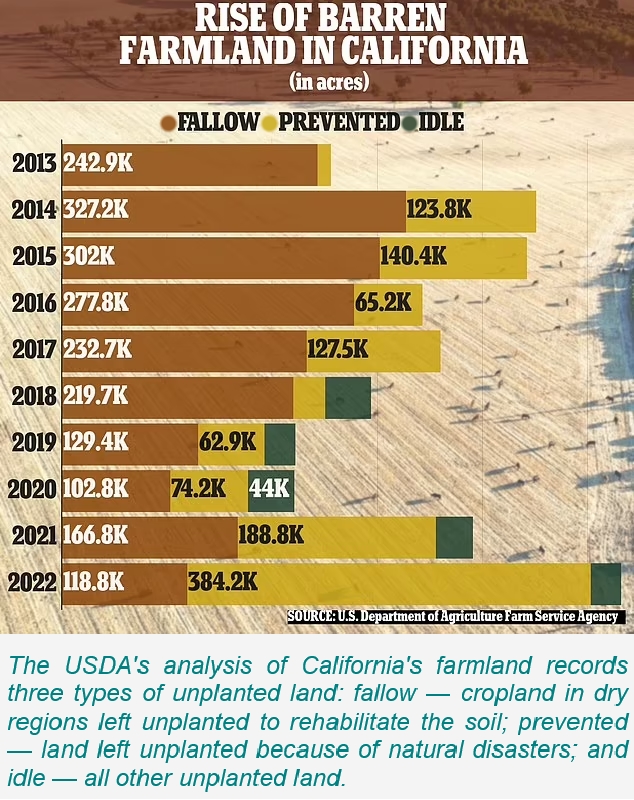

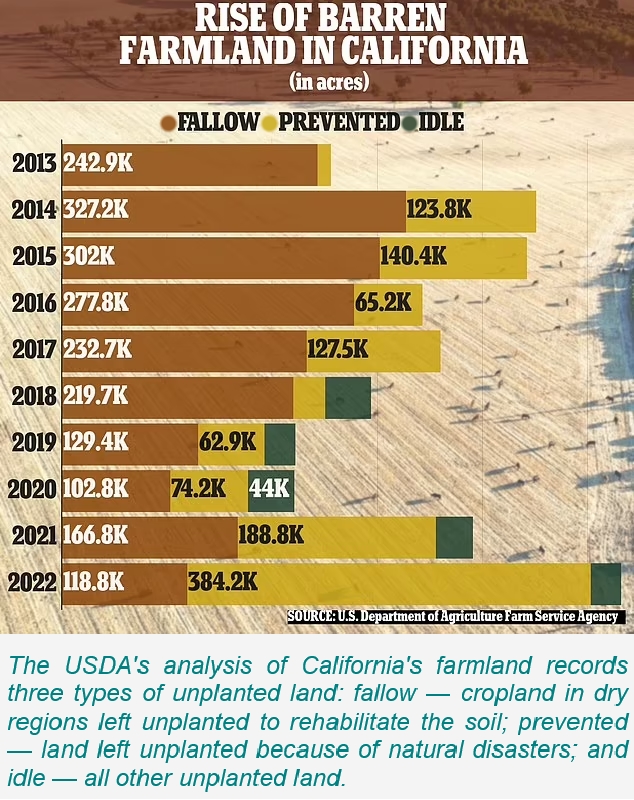

Farmers are getting little surface water from the state’s depleted reservoirs, so they’re pumping more groundwater to irrigate their crops. That’s causing water tables to drop across California. State data shows that 64 percent of wells are at below-normal water levels. Water shortages are already reducing the region’s agricultural production as farmers are forced to fallow fields and let orchards wither. Some 531,000 acres (215,000 hectares) of farmland went unplanted this year because of a lack of irrigation water, the US Department of Agriculture says.

The increase in unplanted land represented a 36 percent hike from the previous year. Experts say supplies of such key crops as wheat, cotton, rice, and alfalfa could become scarce during next year's harvest.

Sources: dailymail.co.uk, reuters.com, gizmodo.com

Near Firebaugh, California, Aaron Barcellos planted just a quarter of the 2,000 acres of his family's fourth generation farm. This summer, he harvested tomatoes two weeks early to prevent further drought damage. "I don't think farming in California has ever been more complex and more challenging, and the drought is a large part of that," said Barcellos.

Near Firebaugh, California, Aaron Barcellos planted just a quarter of the 2,000 acres of his family's fourth generation farm. This summer, he harvested tomatoes two weeks early to prevent further drought damage. "I don't think farming in California has ever been more complex and more challenging, and the drought is a large part of that," said Barcellos.